The G20 Summit in New Delhi partially obscured two important anniversaries. The first of these is recent and well-known — the September 11 attacks by Al Qaida in 2001. This inaugurated the United States of America-led War on Terror in different theatres such as Afghanistan, Iraq and so on. That age now is behind us. How quickly we have distanced ourselves from the global War on Terror is suggested by the fact that Afghanistan is not even mentioned in the New Delhi G20 communique, just as it was not in the Bali communique. In contrast, as recently as in 2021 — the 20th anniversary year of the 9/11 attacks — there was a special G20 Summit on Afghanistan against the backdrop of the return of the Taliban to power in that country.

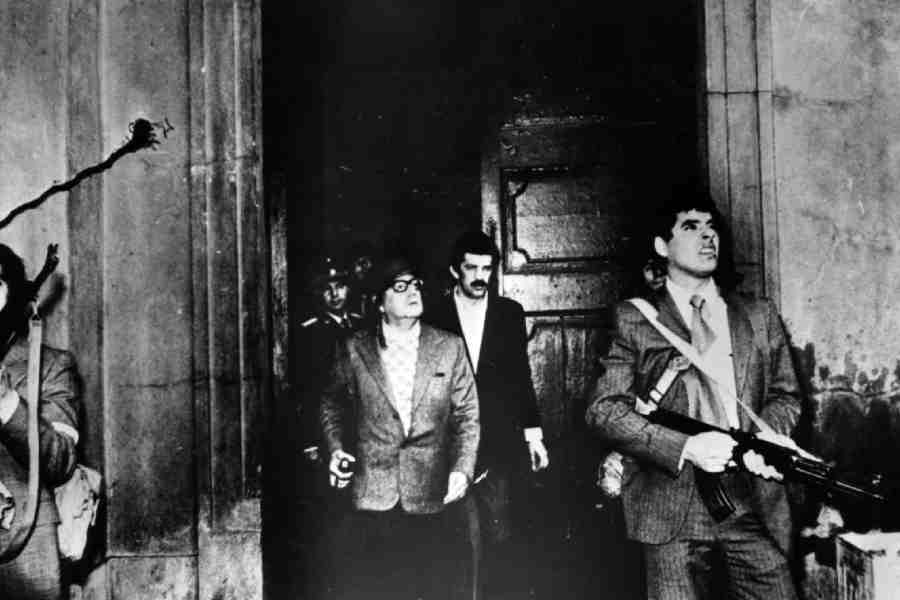

The other anniversary was also a 9/11, but in distant Chile and half a century ago in 1973. A military coup on September 11, 1973 ousted the then president, Salvador Allende. As tanks surrounded the presidential palace and jets overhead fired missiles at it, Allende delivered a final speech over the radio and killed himself — becoming an eternal totem for many on the Left. This was a military coup supported by the right-wing against a socialist president. The fact that this was in the midst of the Cold War and that there was a US plan to disrupt and erode a Left government with the Central Intelligence Agency deploying its full bag of dirty tricks gave this event a narrative consequence that removed it from the narrower confines of purely domestic Chilean politics.

The military dictatorship headed by General Augusto Pinochet as the president then lasted for almost two decades, characterised by extraordinary human rights violations and brutality. The duration of the military regime, however, also reinforced Right/Left faultlines that remain in Chile to this day.

The international resonance of the coup over the years should not be underestimated either. Within a few days, the Chilean poet and 1971 Nobel laureate, Pablo Neruda, died — most likely poisoned — and he had been a strong supporter of the deposed president. Another Latin American, the author, Gabriel García Márquez, referred to Allende as the “Promethean president, entrenched in his burning palace, [who] died fighting an entire army, alone” in his Noble lecture just under a decade later. Over the years, Allende and the coup that deposed him inspired many on the Left and catalysed the human rights movement internationally.

On the 50th anniversary of the coup this year, at a commemoration ceremony on September 11 in Santiago, the Chilean president was joined by the presidents of Mexico (who did not attend the G20 Summit), Bolivia, Colombia and Uruguay. The prime minister of Portugal also attended. Yet, the commemoration itself took place in a divided polity. Pinochet’s coup and his regime had many supporters — and it still does. While international attention usually focuses on the extent of the US involvement in the coup, the domestic faultlines that underwrote it have been durable. To many in Chile, notwithstanding its many excesses, the military regime corrected Allende’s socialist excesses, stabilised the economy and set it on a growth path. In brief, the beliefs and interests that underwrote the 1973 coup remain relevant, even if the possibilities of military intervention may have receded.

Can we contextualise Chile’s 9/11 in terms of our region? There are, of course, no parallels with Chile or Latin America in general, but there have been a multitude of coups in South and Southeast Asia — each coup has its unique identity. What is, however, interesting is how deep the roots of the military can be in widely differing polities.

The return — one completed and the other as yet only announced — of two singular political exiles illustrates this well. In Thailand, the former prime minister, Thaksin Shinawatra, has returned, ending a decade-and-a-half-long foreign exile. He had been deposed in a military coup in 2006. His party had gone on to form the government again after a few years before being deposed in another coup. On his return, Thaksin quickly received a commutation of an eight-year jail term on charges of corruption to escape which he had gone into exile. The jail sentence was reduced to a year and his party reached an agreement with pro-military parties to form a new government. In brief, Thaksin and his party are now allied with the very parties and forces that twice overthrew them in the past.

Lest we simplistically ascribe this to some variant of Southeast pragmatism, it is useful to take note of the fate of another exile whose fortunes we in India follow more closely. The former prime minister of Pakistan, Nawaz Sharif, announced in London last week that he will return to Pakistan on October 21. When that happens, it will end a four-year-long self-imposed exile. He faces corruption-related cases in different courts in Pakistan and already has a lifetime ban from politics imposed by the country’s Supreme Court. Yet, he will return to a much-changed situation — from being the Pakistan military’s bête noire, he is now its favoured ally.

Till as recently as two years ago, such an outcome would have appeared bizarre. Sharif has a quarter-of-a-century-long history of friction and turbulence with the military, the chronology of which includes being toppled in a coup, long periods of imprisonment, exile and so on. His earlier returns to power have been seen as a demonstration of both his staying power as equally the intensity of civil-military confrontation in Pakistan.

But this return may be regarded by future historians as the most surprising, given that Nawaz Sharif and his party are now part of a military-constructed concert. Much as in Thaksin Shinawatra’s case in Thailand, this demonstrates the enormous fluidity of all politics; equally, it shows us that beneath the formal structures of the military in both countries are durable social and political realities that remain relatively unchanging and thus prevail over normative narratives. And yet, both in the case of Thailand and in Pakistan, it would be foolhardy to contemplate that other surprises are not waiting.

T.C.A. Raghavan is a former High Commissioner to Singapore and Pakistan