For the past three years, I have been rummaging through many archives, books and articles trying to piece together the origins, philosophical import and aesthetic intentions behind the symbols that we have chosen to represent our country. The icons I have been interested in include the national anthem, flag, symbol and motto. My enquiry is also an attempt to place them in our present context. In this search, I have stumbled upon many interesting discoveries that raise musical questions.

As many are aware, before the Constituent Assembly officially chose “Jana Gana Mana” as our national anthem, Subhas Chandra Bose did so of his own volition during his stay in Berlin. The song was first played on September 11, 1942, at the inauguration of the Deutsche-Indische Gesellschaft, and then again on January 26, 1943, which was also Bose’s last public appearance in Europe. After setting up base in Singapore, Bose had Mumtaz Hussain, the lyricist from Lyallpur, Punjab, and Abid Hasan, who was by then a major in the Indian National Army, translate three out of the five stanzas of “Jana Gana Mana”. Ram Singh Thakur, the conductor of the INA orchestra, arranged the music. The song began with the words, “Subh Sukh Chain”. But to consider “Subh Sukh Chain” as a direct translation of “Jana Gana Mana” does disservice to both songs. “Subh Sukh Chain” has its own voice and tone. Rabindranath Tagore’s mind is its edifice but the song is an independent soaring seagull.

Many renditions of “Subh Sukh Chain” are available online and almost all are sung in exactly the same tune as that of “Jana Gana Mana”. It has been presumed that there wouldn’t have been any difference in the music. After all, it was just a matter of replacing the text. With the help of the historian and the grandnephew of Subhas Chandra Bose, Sugata Bose, I was able to access an early (1943-44) staff notation of “Subh Sukh Chain” from the Netaji Research Bureau. When reconstructed, it revealed subtle but emphatic differences with its predecessor. It is indeed difficult to articulate those stunning melodic alterations in writing without going into notational specifics. But I will say that every little shift, differentiating quiver, new fastening melodic passage and unusual pause gives this song an individual musical identity. The only rendition that mirrors this notation is that by Lakshmi Sahgal.

In this re-creation, Tagore’s larger-than-life, moving imagination was given an everyday resonance. Even though “Jana Gana Mana” lyrically traverses many emotional states, melodically, it is grandiose, regal and towering. On the other hand, “Subh Sukh Chain” gives us a musical glimpse of an everyday morning on an Indian street, where necessities and playfulness come together in a picturesque, aural portrait. Mumtaz Hussain’s language is also dialectically mixed, the colloquial co-existing with the literary. We know that these lyrics were written to match Tagore’s linguistic and musical meter. Yet, it was not a copy by any stretch of the imagination. It had its own life. It is impossible to say whether the changes in language, semantic gait and spirit induced those melodic novelties or Thakur’s musicality inspired these poetics segues.

But these songs are not two contesting ideas. Instead, they invoke a conversation between two diverse, but elevated, sensibilities. The passion for this land and the need to live in love churn within me as I sing them. Yet, they do not come from the same sonic comprehension of India. Melodies by themselves carry meaning and belonging. Whether or not a person understands Tagore’s or Mumtaz Hussain’s words, we can build free-spirited relationships with each of them that are beyond our ingrained obligations. Just from their sound they evoke tears of sadness and hopeful smiles.

No conversation on “Jana Gana Mana” can exist without referring to its political bête noire, “Vande Mataram”, known as our national song. Despite its tumultuous past, the song has remained in people’s memory. I have sung the first verse many times too. But the tune in which we render “Vande Mataram” is itself a mystery. No one really knows the tunesmith’s name. Some claim that this popular version was Ravi Shankar’s creation, which All India Radio recorded and disseminated.

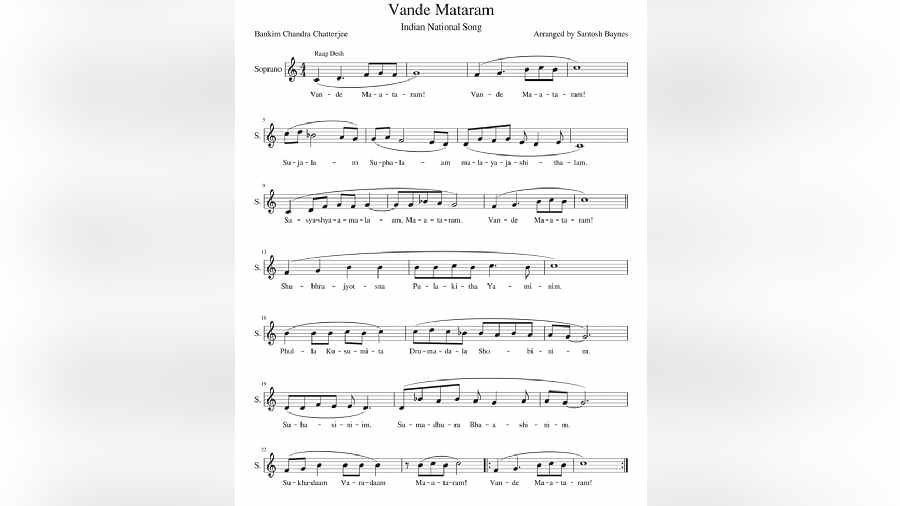

When I filed an RTI petition asking for the authorised notation of the national anthem, the ministry of home affairs directed me to a booklet titled Our National Songs. First published in November 1951 (followed by multiple editions), it contains a short history, the text, English translation and notation of the anthem as well as a brief history, text, English translation and notation for the first two stanzas of “Vande Mataram”. The notation is published in two appendixes; stanza 1 in Appendix K and stanza 2 in Appendix L. The music for the first stanza is attributed to Tagore and for the second to Indira Devi Chaudhurani. The tune given in this booklet is not what we have been singing for the past seven decades. This notation based on Raga Desh was first published in Balak magazine in 1885. Only the first stanza was notated. Later in 1900, the notation for all four stanzas was published in the book, Shotogan. The musical composition is attributed jointly to Tagore and Sarala Devi. There are minor differences between the two notations but they are indeed the same. The Government of India has reproduced the Shotogan notation for the first two stanzas. There are only a couple of textual changes. There is also a majestic rendition of the first verse in this tune by Tagore himself.

Unlike “Jana Gana Mana”, no rules or code were framed to define the manner in which “Vande Mataram” should be sung. Yet, it is quite astounding that the version we have been singing is not the one authoritatively published by the Government of India. Tagore’s melody for Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s words was, in my opinion, far more delicate and beseeching. Our version in Raga Desh is beautiful but it is undeniable that it lends itself to an unthinking salutation because of certain melodic ascendancies and climaxes. Can we separate the chest-thumping and bigotry that “Vande Mataram” instigates from the tune in which it is sung? The song’s role in Bakim’s novel and the socio-political upheavals of the early 20th century are undoubtedly imprinted in the song. But I believe that much of that etching exists in the sound of the music itself. Songs are very different from poems. The fluidity in poetry exists in the abstractive possibilities that words and linguistic phonetics allow. When a poem becomes a song, layers of melodic and rhythmic sound encase every lyrical utterance. In that togetherness, meaning transcends itself and this can go in both directions.

What about the singers? It is likely that in the early 20th century, “Vande Mataram” was heard a number of times in Tagore’s tune, yet it disturbed the Islamic community, and for good reason. So the words and the music are not the only instruments of emotion. The ethical compass of a song does not stop with historicity or its composed melody. It also emerges from the heart of the singers. Whether it is “Jana Gana Mana”, “Subh Sukh Chain” or “Vande Mataram”, what they convey is as much a result of the quality of our mind as it is the songs on their own. When we turn to the dark side, music loses its solicitude.

T.M. Krishna is a leading Indian musician and a prominent public intellectual