Tariffs and the economic consequences of Trump 2.0 are overshadowing all other aspects of the new president’s first 100 days. By the time this milestone is reached at the end of April, it would be a fair assessment that no other American president has so shaken both his own country and the whole world in such a brief period.

If tariffs are likely to win any poll of Donald Trump’s most significant disruptions, then his view that the present borders of the United States of America would benefit from a change will come a close second. Borders loom high in the world view of Trump’s presidency. The claim that Greenland should become a part of the US or the demand to rename the Gulf of Mexico as the Gulf of America animates this. The focus on hardening and further securitising the border with Mexico to curb illegal immigration also points to that conclusion.

It is, however, Canada that really grabs the news. Possibly every aspect of the US-Canada relationship has never been so shaken up as has happened since the onset of Trump 2.0. What had been assumed to be stable water-sharing arrangements and treaties have been opened up, possibly with a view to renegotiating them so that water can be bought from a water-surplus Canada to the drought-prone states in the US.

Even this is overshadowed by the president’s claim that Canada should become the US’s 51st state. The US-Canada border, incidentally the longest land border in the world, was, President Trump said, just an imaginary line as if “done with a ruler”. Whether this is real or a bluff to strengthen his negotiating position is something that nobody quite knows as yet. But that long established borders can be artificial is certainly part of his thinking.

Borders, even those that have appeared as the consequence of a very specific chain of events, can also be surprisingly resilient. In February this year, the German national elections threw up results which showed a clear East-West divide — between the areas that comprised the former German Democratic Republic (erstwhile East Germany) and the Federal Republic of Germany (formerly West Germany). The right-wing and anti-immigrant AfD, or Alternative for Germany, performed strongly in the areas that formed the GDR. The AfD is also anti-EU, anti-NATO, pro-Putin and — to its critics — reminiscent of the Nazis.

Some were surprised that this older division still persists more than three-and-a-half decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Others were not. After all, for many in the former GDR, the reunification of East and West Germany was a traumatic process as integration with the more advanced West had meant deindustrialisation for a start as also the sense that the East Germans were somehow second-class citizens. Such attitudes can endure for long periods.

Some German historians point to the East-West division being much older than the one dating back to 1945. The core support for the Nazis and Adolf Hitler came from the eastern parts of Germany, areas that had once formed part of the old kingdom of Prussia. This had been the more feudal, the more conservative, and anti-Semitic part of Germany. In other analyses, there are even deeper factors behind the East-West division, not least of which is its overlap with the geographical distribution of Protestants and Catholics in Germany with the former predominant historically in the East.

The East-West division of Germany can be seen as what is often termed a ‘phantom border’, one that exercises influences and has significance although its older, legal, and political status no longer exists. The term is often employed in a metaphorical way. Just as phantom pains are felt in a part of the body that is already amputated, similar phantom borders assert themselves as an older, but now defunct, political entity.

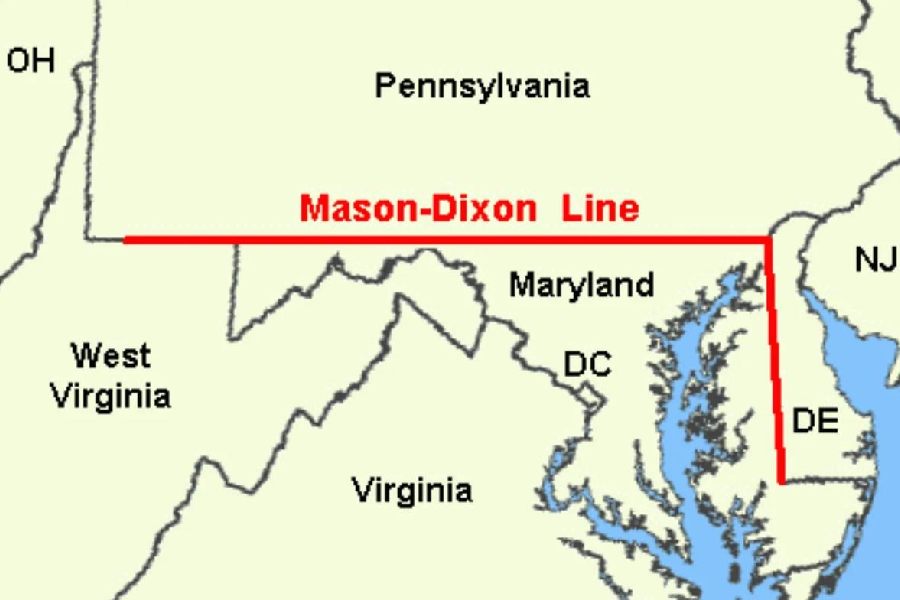

Phantom borders pop up everywhere. Forgotten legal and political borders exercise an outsized influence in terms of governing behaviour. In the US, a staple for discussion for the past two decades, and especially so with the rise of the Trump phenomenon, is the extent to which the Republican-Democrat division of today reflects the North-South division — the Mason-Dixon line — of the US Civil War in the 1860s. That old divide gains visibility in other ways too: for instance, during the pandemic, opposition to the compulsory wearing of masks was much higher on the southern side of the divide. The North-South division overlaid by the urban-rural divides explains much of the polarisation in the US today.

If phantom borders pop up everywhere, it is in eastern and central Europe that they appear most prominent. The term itself was coined in the study of contemporary eastern Europe. This is hardly surprising. Over the course of the 20th century, that region witnessed major surgery multiple times: in the aftermath of the First and the Second World Wars, following the end of the Cold War and the break-up of the Soviet Union and, thereafter, with the civil war in the former Yugoslavia. Europe may well be in the midst of another redrawing of the map of Ukraine although we cannot say for certain what final form this will ultimately take.

What about phantom borders nearer home? India, too, is criss-crossed with them. The proceedings in the 1950s of the States Reorganisation Commission are a testimony to this with regard to our domestic politics. The fact that a number of former ruling princes and princesses still play significant political roles in constituencies that include their former princely states provides a clue to this.

South Asian geopolitics can also be seen through this prism. Whether in Myanmar to our east or in Pakistan to our west, the roots of many current conflicts can be traced to contests between phantom borders and contemporary international boundaries. Thus, the boundaries of Ranjit Singh’s kingdom came to define the western extremities of British India and then of Pakistan. This may not be a phantom border in the strict sense but in a way it is his phantom that stalks Pakistan’s troubled Af-Pak border zone today in the form of the Durand Line.

T.C.A. Raghavan is a former High Commissioner to Pakistan and Singapore