On the eve of Poila Baisakh, Bengali New Year’s Day, the question of Bengali asmita hangs heavy in the air. Is it under siege? If so, from where? Is the eclectic, pluralist soul of Bengal’s culture that is under threat from religious bigotry and narrow-minded fundamentalism? Is it the Bengali language whose present and future are jeopardised? The aftermath of the recognition of Bengali as a ‘classical’ language by the Indian government seems to be a good moment for some reflections on especially the second question.

In 2004, the Indian government decided to create a new category of languages as ‘classical’, determining specific criteria on the antiquity of a language and the nature of extant literature in it. Tamil got this recognition that year. The criteria were revised in 2005, with the ‘antiquity’ requirement raised from one thousand years to a minimum of 1,500-2,000 years. That year, Sanskrit joined the ranks of ‘classical’, with Kannada and Telugu following suit in 2008, Malayalam in 2013, and Odia in 2014. And then, in October 2024, this prized status was accorded simultaneously to Marathi, Pali, Prakrit, Assamese and Bengali, thereby bringing up the number of officially-recognised Indian classical languages to eleven.

Traditionally, a ‘classical’ language is a prestigious, often ancient, language, like Latin or Sanskrit. Such languages are often contrasted with ‘vernacular’ languages, which in Indian history have usually entailed a position of inferiority or powerlessness in relation to ‘dominant’, ‘cosmopolitan’, or ‘classical’ languages. Yet, the assertions of linguistic identity in colonial India — and their imbrication in the rhetoric of community, history, and territory — turned these ‘vernacular’ languages into powerful vehicles that could appear to represent and speak for hitherto unrepresented groups. It was this that shaped the strategies employed in defining the territorial claims of new linguistic provinces both before and after 1947.

Vernacular print cultures mushroomed in different parts of India from the second half of the 19th century onwards and had a critical role in the creation of public spheres in colonial India. In many regions like Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Punjab, Andhra Pradesh, Odisha, Kerala, Gujarat and so on — which, at the time, were included in multilingual colonial administrative units like the Bengal, Bombay, and Madras Presidencies — the explosion of writing on language, literature, culture, and history usually gravitated towards delineating a territoriality of the linguistic community. This territorial element would later provide the spatial substance of the movements for linguistic states.

Interestingly, in Bengal — with its vibrant, vernacular print culture — the project of writing the histories of language and literature was unconnected with a quest for an autonomous territorial identity. Bengalis, because of their early exposure to English, came to dominate the Empire’s subordinate bureaucracy all the way from Punjab to Assam. Unsurprisingly, Odia and Assamese linguistic movements — which eventually took territorial dimensions — originally emerged in response to what was perceived as Bengali ‘sub-colonialism’.

But the history of the Bengali language and literature, including its ‘origin theories’, was not brought into the service of seeking a territorial foothold for the concept of ‘Bengaliness’ because this was never an agenda for Bengal. With the exception of its successful pitch for acquiring the Bengali-speaking areas of Manbhum district from Bihar in 1956, the Bengali vernacular intelligentsia didn’t have to formulate expansive ‘imagined [linguistic] communities’ and submit their territorial-geographical expressions to the various colonial and postcolonial commissions that decided on territorial reorganisations. For, willy-nilly, Bengal was on the other side of the table, being forced to part with large chunks of territory, most notably during the two Partitions of 1905 and 1947.

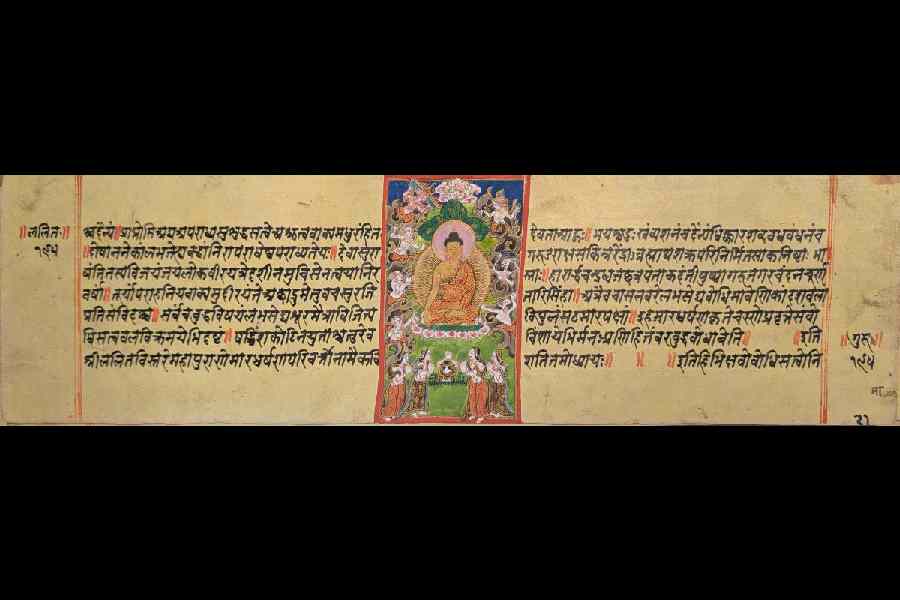

In writing the first history of the Bengali language and literature in the 1890s, the literary scholar, Dineshchandra Sen, was driven not by any project of ethnolinguistic regionalism but by his deep love of Vaishnava and Mangalkavya literature. Sen described the Bengali script as having been derived from scripts prevailing during the early Guptas in the 4th century CE though he referred to a Buddhist text, Lalitavistara Sutra, to claim that the languages and scripts learnt by Gautama Buddha (circa 5th century BCE) included something called ‘Bangalipi’. Sen’s collaborator in this quest, Haraprasad Sastri, collected manuscripts of Charyapadas, mystical poems from Vajrayana Buddhist traditions of eastern India, that were written between the 8th and 12th centuries CE in Abahatta, a sort of proto-Bengali. The linguist, Muhammad Shahidullah, who worked as Sen’s research assistant during 1919-21, pushed the antiquity of this proto-Bengali of the Charyapadas even further back to the 7th century CE, while also citing Bengali terms contained in an 8th-century Sanskrit-Chinese dictionary. He sought to repudiate the claim made by the linguist, Suniti Kumar Chatterji, in his monumental, two-volume The Origin and Development of the Bengali Language (1926), that concrete evidence of Bengali becoming a distinctive language didn’t exist before the 10th century CE.

It’s quite interesting to see that the original application document from West Bengal for Bengali’s ‘classical’ status claimed that the existence of Bengali words in an 8th-century Chinese-Sanskrit dictionary “illustrates with absolute certainty that Bangla must have been the language of communication for several centuries before (columnist’s italics)...” While this may well have been the case, the tenor of this claim involves an unverified element of conjecture. This has often been the case in the instances of imagined ‘placemaking’ that have historically served the cause of regional identity and provincial autonomy movements.

West Bengal seems to have undertaken such a monumental interdisciplinary exercise in establishing the antiquity of the Bengali ‘people’ and the Bengali language and literature — deploying the methods of archaeology, epigraphy, anthropology, history, linguistics, and literary studies — for, arguably, the first time in history. And that too with the objective of gaining a status — two decades after Tamil and one after Odia — that promises, theoretically, to bring in modest gains, like a couple of ‘major international awards’ per year for scholars, a ‘Centre of Excellence’, and a few ‘Professional Chairs’ for the language, to be created in an unspecified future by the University Grants Commission in the Central universities. At a time when adversarial Centre-state relations continue to erode Bengal’s fabric of higher education and the UGC itself stares at an uncertain future, it would be a leap of faith for Bengal’s asmita to ride on these few crumbs of unguaranteed comfort.

It’s anybody’s guess whether the order of awarding ‘classical’ status is skewed in favour of ‘friendly’ states. But the application process obviously involves a lot of competitive lobbying, as can be seen in the pressing parliamentary questions constantly raised by legislators about whether the government is considering granting ‘classical’ status to such and such languages. It was exactly these kinds of bargaining and negotiations that drove the demands for linguistic states in the 20th century and are now being reenacted on a much lesser stage. Changes in the eligibility criteria introduced by the Central government — most notably, the enhancement of the minimum ‘antiquity requirement’ from 1,000 years in 2004 to 1,500-2,000 years at present — have also pushed candidate states towards ever more desperate and conjectural origin theories about their languages which can sometimes deviate from peer-reviewed academic research.

The funding that a ‘classical’ status brings is, often, a pittance. To cite two recent examples, Odia and Malayalam both received this status in 2014, but in the decade since then, both have received an average annual sum of around Rs 38 lakh (according to figures given by the Press Information Bureau). Can this, as the ministry of culture claims, create significant employment opportunities, especially in the academic and research sectors, fund “the preservation, documentation, and digitization of ancient texts in these languages”, and “generate jobs in areas such as archiving, translation, publishing, and digital media”? Will Bengal receive even that much, especially in an era when most of its dues from Central schemes and projects are kept on hold? This, again, is anybody’s guess. One only hopes that the laboriously researched volume that the Classical Bangla application document represents doesn’t turn out to be much ado about a little something.