It feels strangely disquieting to celebrate Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav amidst the untold suffering caused by the pandemic. Perhaps the anxiety about an uncertain present and an even more unpredictable future compels us to turn to the past and deliberate on the unexplored aspects of the Indian national movement in the hope that the return will rejuvenate the present and the future. This path is guided by T.S. Eliot’s concept of the three imbricating phases of time: “Time present and time past/ Are both perhaps present in time future,/ And time future contained in time past.”

In contrast to nationalism in the modern West that disinherited the past and the pre-modern, nationalism in India recalled the past, thus connecting the present with its history. The range of the past that is remembered is rather wide — from Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay recalling Sankhya to Swami Vivekananda the Vedanta, to Babasaheb Ambedkar’s recalling of Kapila and Buddha.

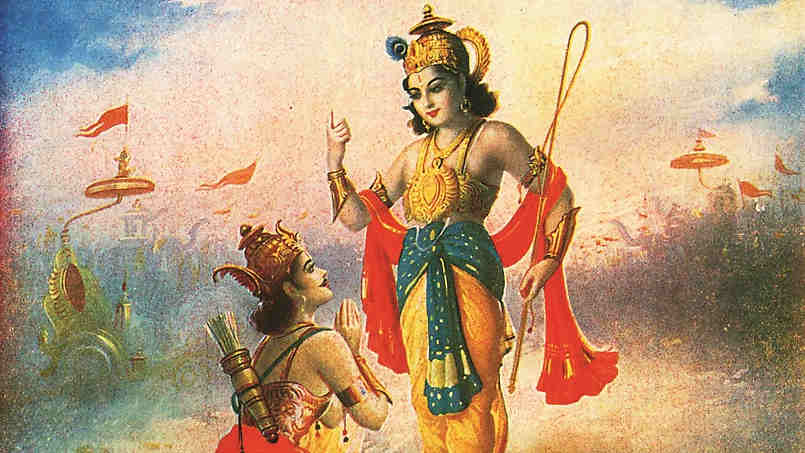

The Bhagavad Gita, a part of the epic, the Mahabharata, is yet another interesting work recalled for the freedom movement. In his well-known commentary, Shrimad Bhagavad Gita Rahasya, Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak outlined similarities between the war of the Pandavas and the Kauravas and the Indian struggle for freedom against the British. He also found justification for the use of violence against the British in Lord Krishna’s advice to Arjuna.

The intention behind refurbishing the ancient text with a new commentary was to energize Indians and rouse them to participate in the freedom struggle. Tilak, like Getafix in the Asterix series, brewed the magic potion from this ancient text. Nations in the West were based on modern political ideals, cemented by path-breaking discoveries in science and innovations in technology that kick-started industrialization. The developments in their present thus contributed to their future. However, British imperialism used these modern resources, political ideas, science, technology and industry to colonize and exploit India, robbing Indians of the opportunity to build their future with the resources from the present. The ingenuity of Tilak lay in quickly grasping which options were closed and the ones that could be explored as alternatives. In the next phase, Mahatma Gandhi continued the legacy of Tilak, his guru, by continuing to rally around the Gita but he interpreted it differently.

There are two parts to Tilak’s rendering of the Gita. One, he only used the Gita, not the larger epic. Two, he interpreted the Gita as justifying violence. Like Tilak, many have used the Gita to support their ideas of the national movement. However, in my limited reading, at least at the national level, the Mahabharata has been used by only a few. In addition to Gandhi’s Essays on Bhagavad Gita and Shashi Tharoor’s The Great Indian Novel, the Mahabharata and the national movement are implicit in two more works — Sri Aurobindo’s Savitri: A Legend and a Symbol and Ashis Nandy’s The Intimate Enemy. While Sri Aurobindo draws out the underlying parallels between Savitri losing her husband to Yama, the god of death, and India losing its freedom to the British, Shakuni is the underlying symbol in Nandy’s account of the loss and recovery of the self under colonialism. To make a limited use, like Shakuni, colonialism is India’s intimate enemy. Gandhi, however, uses the epic to formulate the programme of non-violence for the national movement.

To return to Tilak, there is a radical difference between Tilak’s and Gandhi’s interpretations of the Gita. For Tilak and many others, the Gita promotes violence, as Lord Krishna advises, nay, incites a reluctant Arjuna to fight the war. However, going against the entire tradition of interpretations of the Gita, Gandhi found a justification for non-violence and a denouncement of violence in this text. He accomplished this by making two important moves: one, from the part to the whole, that is, from the Gita to the epic, the Mahabharata and, two, from the content to the context.

From ancient times, the Gita has been discussed as an independent text. Gandhi, in contrast, saw a close relationship between the Gita and the Mahabharata. He then moves to the context — Vyasa, Gandhi said, narrated the Mahabharata “to depict the futility of war”. The epic was recounted by the sage, Vaisampayana, a disciple of Veda Vyasa, to Janamejaya, the son of Parikshit, at the Sarpa Sastra yajna to dissuade Janamejaya from killing all living snakes merely to wreak vengeance on a serpent that had disturbed the penance of Parikshit.

On a close reading of Gandhi’s work on the Gita, tweaking it a bit here and there while remaining within the purview of the text, we can discern a dichotomy between the content of the epic that essentially promotes and justifies violence and the context of the narration, which was to dissuade from committing violence. This relationship between the context and the content, part and whole, is a unique distinguishing feature of this epic with reference to world literature. Gandhi was the first to recognize this. His interpretation is a rare academic adventure in hermeneutics by a politician at a global level. More importantly, this intellectual feat was deployed as an instrument in support of the national movement.

To return to Eliot, while he does propose the imbricated relationship within the three phases of time, the latter part of the poem is a reaction to the fractured relationship between the present and the past in the West. Thus, Eliot is not as useful to understand the different relationships between the past and the present in India. For Eliot, the possibilities from the past are mere abstractions and in the realm of speculation. However, Tilak successfully demonstrated that the texts from the past are solid actualities. Unlike in Eliot, where the passage was not taken, and the door never opened, Tilak did take the passage, which opened up new horizons for the Indian national movement.

It is the divergent relationship between the present and the past that makes the Indian model different. Recognizing this is not tantamount to endorsing it. In fact, on the occasion of Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav, we can resolve to explore new avenues in finding out creative solutions to both actual and possible problems in Indian society, taking inspiration from our national leaders from our immediate past.