|

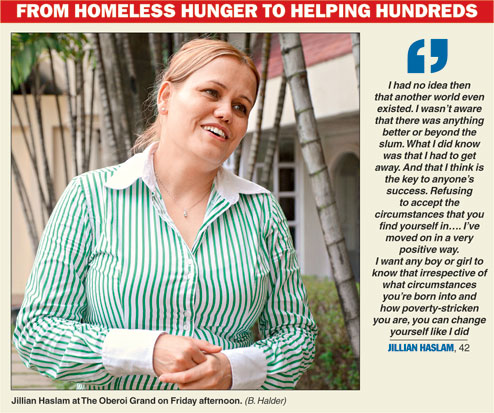

Jillian Haslam, a 42-year-old British woman, was born in Calcutta of parents who did not leave the city after British rule ended in 1947 and brought upon themselves very dark times.

As the fifth of 12 siblings, many of who died of malnutrition, Jillian the child was trundled around streets, under staircases, behind people’s houses where she found a home before ending up in the slums of Kidderpore and living off charity till she left the city at 17.

She lived in Delhi for a few years, got selected by Bank of America where she soared with her schemes and plans of corporate charity, was made president and then rewarded with a special package with which she migrated to London. She took her siblings back home one after another.

Today she is a motivational speaker, trainer and author and connected with the likes of Bill and Hillary Clinton. She has written a book on her life which British screenplay writer Neil O’ Neil has picked up for a film script. She secretly wishes that Julia Stiles plays her if the film is made “because I’ve watched all her films and I think I look a little like her”.

Despite memories of her morbid past and the millionaire life she now has in London, with her three-storeyed house, two cars and a company that offers coaching and training services across the UK and internationally, she wants to return to Calcutta.

Over to Jillian Haslam, the fair blonde British girl with a very Indian accent who still gets her gender all mixed up when trying to speak Hindi and Bengali!

‘We were like beggars’

|

My parents were both British and were born right here in central Calcutta. 1n 1947, when India got her independence, the British were given one year to leave the country and go back. So, hundreds of families went back to England, but not my Dad, who was in the army.

I was born in 1970 and that was when he had his second heart attack. Mum moved him to the Salvation Army where they took him in free. As my Dad’s health deteriorated and he remained in the Salvation Army recovering, we fell upon very, very hard times.

My sisters and I would hold on to my mother’s skirt as we started moving home from under the stairs to behind people’s houses and taking shelter in verandahs. Sometimes when it would rain, we’d go asking people if we could sleep in front of their door under the shade. We were like beggars. I saw my mother take up odd jobs of cleaning clothes or washing utensils.

When I was around five, Mr Nazareth, a south Indian gentleman, approached my father to teach in a small school in Dum Dum. So we packed up and went to live there. We were excited to have a home — two small rooms and a verandah. I remember when my twin siblings died of malnutrition and poverty at six months. We didn’t have the money to buy coffins so a villager got a wooden tea case and my mother put them in the box. I remember my Dad taking the case and heading out with the twins and never speaking about it again.

Months later, one of the villagers came and told my Dad that my sister Donna, who was around 13, would be kidnapped. She was very blonde, had blue eyes and very fair. In the dead of night we left the Dum Dum house, on a local train, in the clothes we stood in.

We came back to Calcutta. Mum took Dad back to the Salvation Army as he was again ill. We went to live under a flight of stairs, in a lane off Prinsep Street, infested with rats and cockroaches. We stayed there for more than nine months. My mother had a plastic sheet on which we would sleep. Food and clothes, she would fetch from the Sisters of Charity.

My sister and me were called “sada choohas” everyday, but more out of cheap thrill than hatred. We learnt to survive in the darkest of lanes. There was a time when my sister and I fell so ill that Mum asked an elderly lady if she’d keep us. She agreed but for some reason she didn’t like me. She had a little toilet infested with cockroaches where she’d lock me up in the evenings and turn off the light, to teach me a lesson. I was so traumatised that I’d start crying when I’d see the sun go down. My Mum noticed that I was not myself and she took us from there. It was the happiest day of my life. We went straight back under the stairs but we were prancing and singing out of joy.

Slowly my father got better and we got a room in Kidderpore, in a proper slum. A tiny room with a verandah, but we were super excited because it felt like our first home. Worms used to come out of the ground at night and big bandicoots. At first there was no electricity, there was no water nearby.... I was eight when Neil my brother was born and Vanessa and I were put into the St. Thomas’ boarding school. After Neil, Susan was born.

‘I’m going to fight’

Susan would have been my fifth sibling to die of poverty and malnutrition. I was 10 and when the doctors were giving up on Susan, I thought to myself that I’m not giving up. I’m going to fight and do what I can. Susan needed milk, so I ran to this little tea shop everyday and managed to get some milk, look after Neil and pray that Susan lives. She survived.

My Dad got another heart attack and my Mum started keeping me away from boarding more and more to look after the little ones and as a child I enjoyed it. Yet, I’d win the progress prize in school and my Mum got a feeling that even if I spent more time at home, I was bright enough to pass my exams. That’s how it continued for years.

During my teens, every boy wanted to touch my sister and me and get friendly. March was horrendous because the entire Holi month boys in the area would throw water balloons, sometimes quite hurtful because they’d aim at our breasts. Diwali time too was hard because boys would throw chocolate bombs at us to see us jump in fright. Even today I can’t take the sound of a balloon bursting.

There’d be people who’d tell me and my sister ‘you be Dharmendra and you be Hema Malini and dance for us, we’ll give you bhuttas’ and we’d do it not realising they were being horrible to us. When you’re hungry, you don’t think of anything else.

I had no idea at that point in time that another world or another country even existed. I wasn’t aware that there was anything better or beyond the slum because we never left it.

What I did know was that I had to get away. And that I think is the key to anyone’s success. Refusing to accept the circumstances that you find yourself in. The minute you make that decision that ‘I refuse to accept what’s happening to me’, the mind starts to channel all the ideas and ways for you to get yourself out of the situation. The minute you start accepting your fate and life, you will always be reduced to accepting that.

I finished my free schooling in St. Thomas’, I was 17 years old and I moved to Delhi to my elder sister Christine who hadn’t faced what we had faced. I did a secretarial course and got started on small jobs in foreign liaison offices.

In between my mother got cancer and was in colossal pain. So to see her alive, I had to take her to Delhi, and my brother Neil. Mum passed away in my house, she was only about 50. Till then I had been working for survival, money and trying to save my mother and little ones.

Soon after I was interviewed for Bank of America with hundreds of girls and got selected, a part of me became unstoppable. I had joined as executive secretary to the CEO and very soon I became the president and head of the charity and diversity network. I loved the job. I was always passionate about charity and helping people. I won several awards for the bank. Our CEO was very impressed and gave me a special package after five years.

I used that money to relocate to the UK after which I took my siblings Vanessa, Susan and Christine to the UK, one by one.

I had met my husband in Bank of America, Delhi. We married in May 2000 and left together for the UK.

I joined RBS in London. I worked for 10 years with the bank and then I went part-time in 2010 because I decided to write my autobiography, not because I wanted to tell people, look what happened to us. I’ve moved on in a very positive way. Since I have a past I want any boy or girl to know that irrespective of what circumstances you’re born into and how poverty-stricken you are, you can change yourself like I did.

I also started training to be a public speaker and getting my business on the ground. From last year, I’m completely on my own to continue my charity work and as a motivational public speaker.

By the way, Susan, who had once almost died, topped her university in London. She did so well that they put up her photographs on the buses and trains in London as an example of Asian kids moving to the UK! She’s married now and settled in Australia. I feel very proud.

‘My heart is in Calcutta’

Even now as I live there, I live more here. I know I live in Britain and there are thousands of charities that I can work with but my heart is here in Calcutta, my place of birth. I can’t help that. I want the world to see that it’s the poorest of the poor who have the biggest hearts.

Success lies in being very rooted and not forgetting where you came from. I have never believed in trying to talk like a foreigner or going abroad to become someone I’m not.

I come back to Calcutta every year. I do a lot of charitable work for Calcutta and Delhi and want to do it on a larger scale now because I have the means to. If I could I would move back to Calcutta tomorrow. I hope to soon.

I’ve never forgotten who I am.

|

What is your message for Jillian? Tell ttmetro@abpmail.com